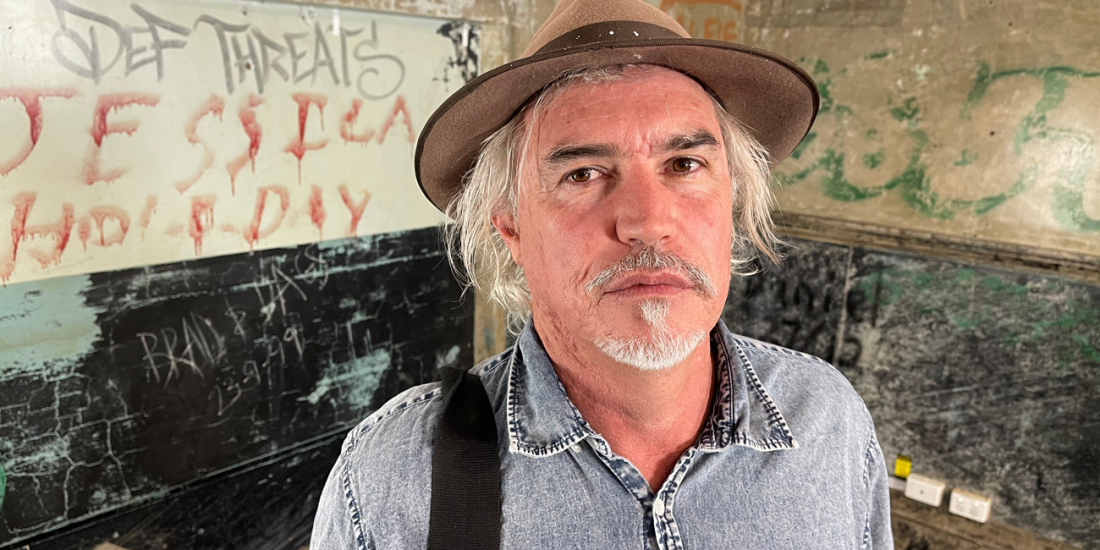

Andy Forbes, artist and curator, TRANCEPLANT

It felt more like a paranormal event that we all witnessed but would spend the next few decades trying to convince other people it actually happened ...

In 1994, a group of adventurous and visionary artists gathered at the Brisbane Powerhouse – then a dilapidated shell – to stage TRANCEPLANT, an immersive ten-night large-scale performance and installation event. An amalgam of heat, noise and mania, TRANCEPLANT was a one-of-kind happening – quickly going down in the history books as a singular and pivotal moment for Brisbane’s arts scene. Over time the event has become a thing of legend – an experience that has yet to be replicated some 26 years later. A group of TRANCEPLANT participants and curators will be sitting down at the site of their monumental undertaking to chat about the event itself and its legacy. We took the opportunity to chat with curator Andy Forbes about what went down over the ten-night season and his reflections on the event’s legacy more than two decades on.

To start, we’d love for you to take us back to 1994 – specifically the time around TRANCEPLANT’s genesis. What was the overarching goal and conceptual drive behind Omniscient Gallery’s ambitious undertaking?

Omniscient Gallery – me, James Dabrowski and Richard Mansfield – received an Arts Queensland project grant for a site-specific installation, so we were looking for a space and environment that would be inspirational to not only us but to a range of different art-forms, circus, music, performance, video, rave, and fine art. We wanted to create an immersive hybrid event and the New Farm Powerhouse – with its colossal architecture, its proximity to The Valley, its decaying aesthetic and its capacity to take the audience and the artists on a wild journey – unequivocally achieved that.

We’re curious about the state of Brisbane’s art scene as it was at the time – can you describe the prevailing attitudes and perception towards local artistic endeavour in the city in 1994?

Brisbane in the 90s on the surface seemed oppressed and the least-exciting city in Australia, but underneath that perception there was a thriving and edgy creative community that was collaborating and experimenting outside of the proverbial box. Livid Festival spawned the cult of rock festivals in Australia, bringing international alternative music and festival arts into focus – Omniscient became part of creating work alongside those musicians and artists. We were one of a bunch of artist-run spaces at the time, which helped fuel the scene. 4zzz was relentless in supporting this alternative movement, as was print-media mags like Time Out, Rave, Artworkers Alliance and Eyeline. The scene was accessible, inclusive and very different to the Melbourne and Sydney scenes that seemed more commercially driven.

It’s hard to imagine the Brisbane Powerhouse as ever being anything other than the vibrant cultural hub it is today, but in the early 90s it was derelict and abandoned. What was it about the structure that you and the rest of the participants found alluring?

Before we had permission to use the Powerhouse, we would break in and smoke up some ideas. We loved the post-apocalyptic look – abandoned, toxic, and dangerous. In some ways it reflected the sentiment that we and other artists were feeling in Brisbane. The demise of an old way of doing things, it was a symbol as well as an immense playground with no rules. You could burn shit, you could swing from the rafters and you could improvise. It was not institutionalised, it was not a white-wall art space, it was not a theatre with seats – it was the beginning of the arts community claiming the Brisbane Powerhouse.

Several multi-disciplinary works, ten nights and one hundred performers per night – TRANCEPLANT sounds like it was a huge operation. For those who didn’t manage to glimpse the event in person, are you able to set the scene and fill us in on how it took shape?

Given a hard hat upon entry, you’re greeted by a legless transexual with a militant sidekick who comically deliver strict instructions on how you would move through the space. Up the pink-glitter stairs you are confronted with an encroaching pool of fire at your feet – gas-filled balloons explode as they fly up to a shattered fifty-metre-high ceiling. A giant tower rolls in with a screaming Hitlerian madman at its summit – now surrounded by naked stilt walkers crying over plastic baby toys and breathing fire. You anxiously gaze down into the polluted waters of the Powerhouse pits, where modern primitives make fires from money that falls from the sky.

Told to abandon ship by a lady with a bull horn, a man covered only in cling wrap grabs at your ankles as you try to escape up the stairs to another level. To calm you down, your perverse hosts sing ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’ before you are then corralled into a Chernobyl-like control room. A drag queen fights for dear life with a feral cyborg and you’re forced to the window’s edge. It becomes deathly quiet – you can hear below a siren singing from within a tall blue-lit fountain that surges water over her and the river’s pier. You’re assaulted by the sounds of industrial-metal guitars that rocket through the building (their origin a band hanging from a platform), while below a woman wearing a wedding dress floats in the garbage lake, battling the band with her angelic voice. You are drawn to the spotlight, which focuses on a strong-man who swings his tattooed circus partner around his body like a pair of nunchucks. The vignette finishes with her ramming his head into the toilet bowl and smoking a cigarette.

Now, a ten-metre video wall projects DNA sequences while a smoke-breathing stilt-walking dragonfly dances beside the digital montage. You start wondering how much more you can endure when the entire building begins to be played like a mechanical drum – creatures creep out from their chemical crevasses and start banging on the railings and structure. Above you, spanning the entire industrial tomb, are lines of petrol-soaked rope bursting into flames. There are sirens, alarms, police, fire fighters all around. You’re told to exit but you’re not sure if this is part of the show or if you are in serious danger. Returning your hard hat, the roller door is shut fast behind the last evacuating participant.

Okay, wow. That sounds incredible and intimidating in equal measure. There must have been a lot that occurred over the ten-night festival – what moments or happenings ended up being particularly memorable for you, or best encapsulate the overall experience?

A moment that symbolises the whole event was the ‘Fire Sculpture’, created by Basis who rigged the petrol-soaked rope throughout the space. The rope was lined with gunpowder so, when ignited, it went off very quickly. I had moved the audience to a safe viewing position for the performance, and when I thought the sculpture was done I instructed the crew to put out the burning rope with fire extinguishers. As the audience moved under the now smoking rope it suddenly lit up again. The audience gasped, I guess thinking perhaps it was part of the show or it had gone out of control. By then I was praying to my own patron saint of the arts, Lucifer, to deliver us from hospitals and litigation.

More than two decades on, TRANCEPLANT is regarded as a pivotal moment in Brisbane’s cultural revolution. Did TRANCEPLANT feel like a phenomenon at the time? When did you realise that it was an event?

TRANCEPLANT felt very special at the time, but I’m really only unpacking it now. It was the high-tide mark for site-specific installation art in Brisbane – there was a synergy and trust with the arts community and there was a snowball effect of involvement because of the Brisbane Powerhouse. Our production had seemed to work, as there was excitement that we had achieved something new. But, like the artworks within the show, it was also fleeting. We were shattered, broke, and had no drive to create anything like that again. It was a monster like Mary Shelly’s Prometheus – a beautiful creation to be feared and it was lost like tears in the rain, to quote Bladerunner. Maybe a paradigm-shifting event but for me, it felt more like a paranormal event that we all witnessed but would spend the next few decades trying to convince other people it actually happened.

Looking back, what do you believe to be the biggest impacts the festival had on the local art landscape and how do you feel that might be reflected in Brisbane’s contemporary scene?

Perhaps the concept of where and how we experience art was the biggest impact we had on the art landscape. We unintentionally stole the building and defined it as a cultural precinct 27 years ago and we demonstrated what its potential was. I hope that the event inspired and continues to inspire artists and producers to manifest work beyond the traditions of art galleries, theatres, museums, circus tents and music venues. The grant from the Brisbane City Council is testament to the commitment of the Brisbane Powerhouse to create an online archive to preserve this historically important event. We are excited to be launching the online archive with the Brisbane Powerhouse on Wednesday May 12, and intend to continue searching for contributions. The celebration on the 12th will also include space to record your experience if you were lucky enough to be a part of the original event.

You’ll be reuniting with fellow TRANCEPLANT artists/performers Jay Younger, Anthony Babicci and Kiley Gaffney to discuss the event with ABC Radio’s Rebecca Levingston for Writers + Ideas – are there any stories or perspectives you’re eager to hear about from your collaborators?

Yes – I’m wondering if anyone found my keys.

You were only a few years into your artistic career when TRANCEPLANT took place – how did the experience inform your own multi-disciplinary practice and shape the way you approached future site interventions from a conceptual and organisational standpoint?

TRANCEPLANT was scary and stressful, but at the same time it gave me an incredible high. From an organisational standpoint it was a hardcore learning curve in what to do and what not to do in your art practice. I wanted to do large-scale collaborative installations, I wanted elements of improvisation and spontaneity, I wanted more control over the environments, and I wanted it to be interactive. So, all the things I learnt from TRANCEPLANT were very important – risk management, responding to the site, directing, and producing, managing artists, managing budgets, the importance of documentation, dealing with the unpredictable nature of an interactive audience and telling your story. I aligned myself with festivals rather than arts funding, theatres, or art galleries as it was faster to get funded and approved for projects, plus the audience was already there. I made theatrical installations for many festivals over the years that achieved a lot of the elements I was looking for.

Finally, we’d love to know what is inspiring you these days. Is there a stimulating force that is really getting the creative juices flowing?

Im excited to be developing with Guy Mansfield a three-part documentary series starting with the TRANCEPLANT story, followed by the ‘Tent of Miracles’ – a twenty-year showcase of our Splendour in the Grass installations – before culminating in the bizarre and loveable story of ‘Wacko and Blotto’, the cult hit that toured the festival circuit for many years.

On Wednesday May 12, Andy Forbes and fellow TRANCEPLANT participants Jay Younger, Anthony Babicci and Kiley Gaffney will sit down with ABC Radio’s Rebecca Levingston at Brisbane Powerhouse to discuss the creation, execution and legacy of the ten-night festival for Writers+Ideas. The event is taking place as part of Brisbane Powerhouse’s 21st birthday celebrations. You can purchase a ticket here.